Chromatin integrity and function

Overview

Cells must duplicate their genomes with high fidelity and efficiency to ensure the accurate transmission of genetic information to daughter cells. This involves both the replication of DNA and its proper assembly into chromatin, processes that are vulnerable to a variety of stress conditions. These stresses can compromise DNA integrity and disrupt the pattern of nucleosome-associated epigenetic modifications, both of which are associated with genetic disorders and oncogenesis. Given the multitude of physical, chemical, and genetic factors that can interfere with the progression of replication forks, genome duplication is a complex and highly regulated process. Replication stress can lead to fork stalling or breakage, which in turn activates distinct and overlapping cellular responses aimed at preserving genomic stability. Our primary objective is to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that respond to stressed replication forks, with a particular focus on the role of chromatin assembly in safeguarding genome integrity during these challenges.

Recent Research Highlights

A major source of genetic instability is associated with the encounter of the replication fork with DNA adducts that hinder its advance. In this case, replication fork stability and genome integrity are maintained by a number of error-free and error-prone mechanisms that help the fork to pass through the lesions and to fill in the gaps of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) generated during the process of fork blockage and lesion bypass. Consequently, this DNA damage tolerance (DDT) response is essential for cell cycle progression, genome integrity, and cancer avoidance. DDT relies on homologous recombination (HR) and translesion synthesis (TLS) mechanisms to fill in the ssDNA gaps generated during passing of the replication fork over DNA lesions in the template. Whereas TLS requires specialized polymerases able to incorporate a dNTP opposite the lesion and is error-prone, HR uses the sister chromatid and is mostly error-free. We have previously reported that the HR protein Rad52 acts in concert with the TLS machinery to repair MMS and UV light-induced ssDNA gaps through different non-recombinogenic mechanisms. Specifically, Rad52 facilitates the recruitment of the Rad6/Rad18 complex, required for PCNA ubiquitylation and subsequent recruitment of the TLS polymerases. Therefore, Rad52 facilitates the tolerance process not only by HR but also by TLS, providing a novel role for the recombination proteins in maintaining genome integrity. Apart from its role in the DDT response, HR is critical for the repair of DSBs, one of the most deleterious DNA lesions. Accordingly, it has been proposed to play a major role in the repair of broken forks, even though this process is scarcely known. Currently, we are advancing in the following mechanisms:

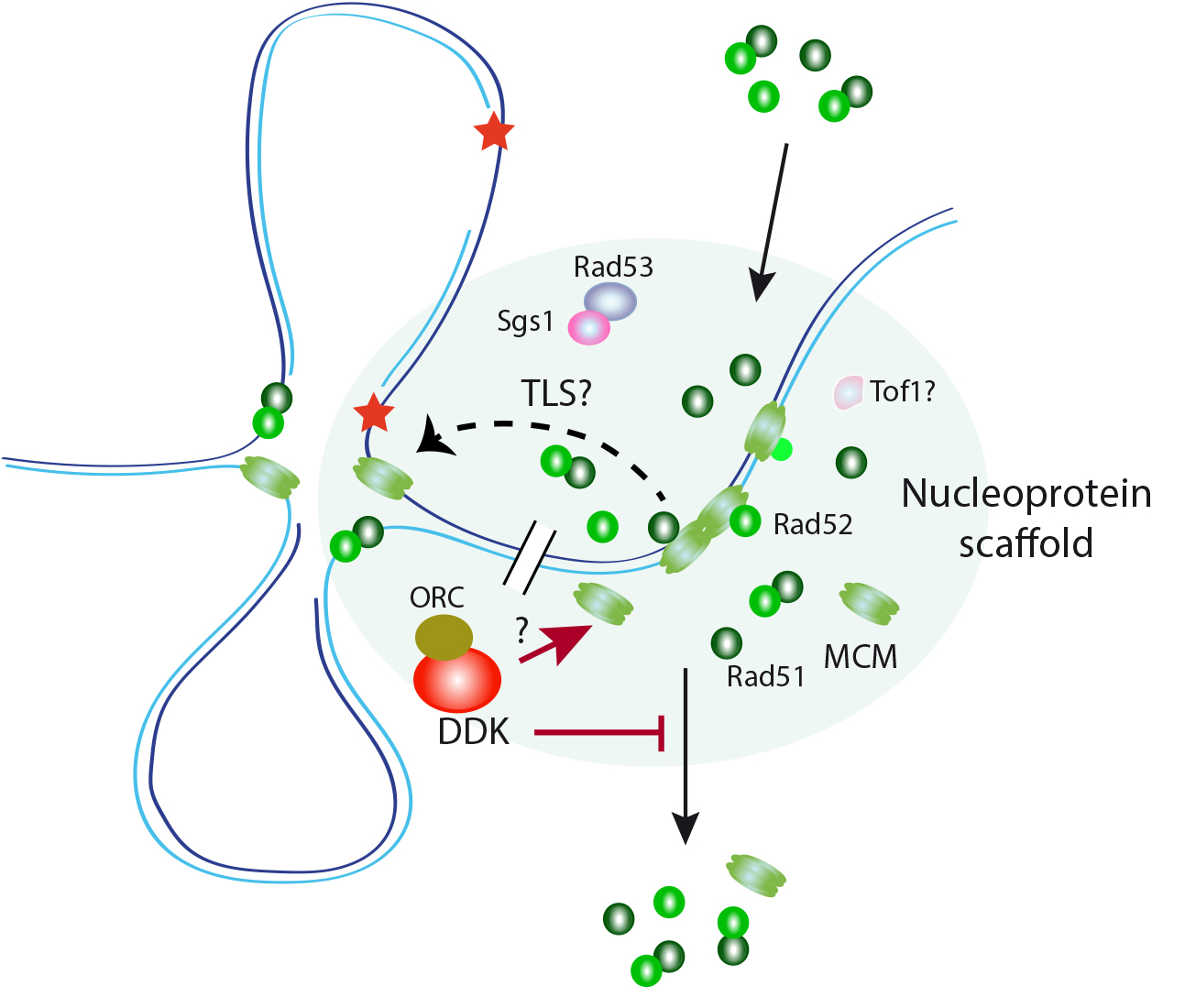

1. A role for DDK-regulated MCM/Rad51 interactions in controlling the DDT response. The recombination proteins Rad51 and Rad52 physically interacts with the MCM helicase from yeast to human cells. We have shown in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that these interactions occur in a nuclease-insoluble scaffold enriched in replication/repair factors. Rad51 accumulates in a MCM- and DNA binding-independent manner and interacts with MCM helicases located outside of replication origins and forks. MCM, Rad51 and Rad52 accumulate in this scaffold in G1 and are released during S phase. In the presence of replication-blocking lesions, Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK) Cdc7 prevents their release from the scaffold, thus maintaining the interactions. We identified a rad51 mutant that is impaired in its ability to bind to MCM but not to the scaffold. This mutant is proficient in recombination but partially defective in ssDNA gap filling and replication fork progression through damaged DNA. Therefore, cells accumulate MCM/Rad51/Rad52 complexes at specific nuclear scaffolds in G1 to assist stressed forks through non-recombinogenic functions (Figure 1).

2. Non-Canonical Roles of the MCM Helicase and the RNR Ribonucleotide Reductase in Replication Stress Response: To further investigate the role of MCM in the DNA damage response, we explored its interaction partners under conditions of replicative stress. Our results reveal that MCM physically interacts with the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) complex and its regulators, including the Dun1 kinase. These interactions, observed in small MCM and RNR subpopulations, are independent of their primary subcellular locations, increase in response to DNA damage, and, in the case of the Rnr2 and Rnr4 subunits of RNR, depend on Dun1. Notably, partial disruption of MCM/RNR interactions leads to defective release of Rad52 from DNA repair centers—without affecting RPA release—despite successful repair of the lesions. This phenotype is associated with hypermutagenesis, though independent of dNTP levels. Our findings suggest that a specifically regulated pool of MCM and RNR complexes plays a non-canonical role in maintaining genomic stability by preventing persistent Rad52 foci and reducing hypermutagenesis.

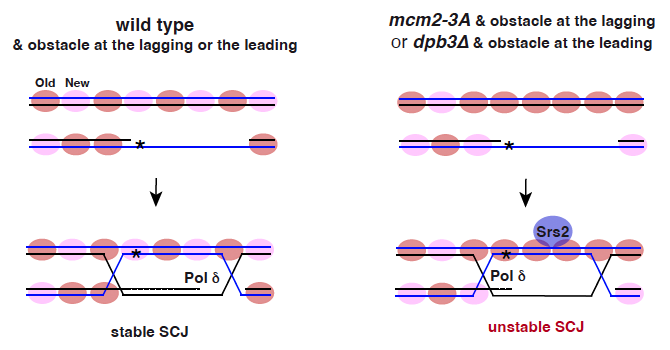

3. Impact of Parental Histone Recycling on DNA Repair Mechanisms: Consistent with the co-regulation of DNA synthesis and nucleosome assembly, we have demonstrated that mutations impairing parental histone recycling during DNA replication result in defects in the recombinational repair of ssDNA gaps. These gaps arise from DNA adducts that impede replication and are subsequently filled by translesion synthesis. These recombination defects are in part due to an excess of parental nucleosomes at the invaded strand that destabilizes the sister chromatid junction formed after strand invasion through a Srs2-dependent mechanism. In addition, we have shown that a dCas9*/R-loop is more recombinogenic when the dCas9*/DNA-RNA hybrid interferes with the lagging than with the leading strand, and this recombination is particularly sensitive to problems in the deposition of parental histones at the strand that contains the hindrance. Therefore, parental histone distribution and location of the replication obstacle at the lagging or leading strand regulate homologous recombination (Figure 2).

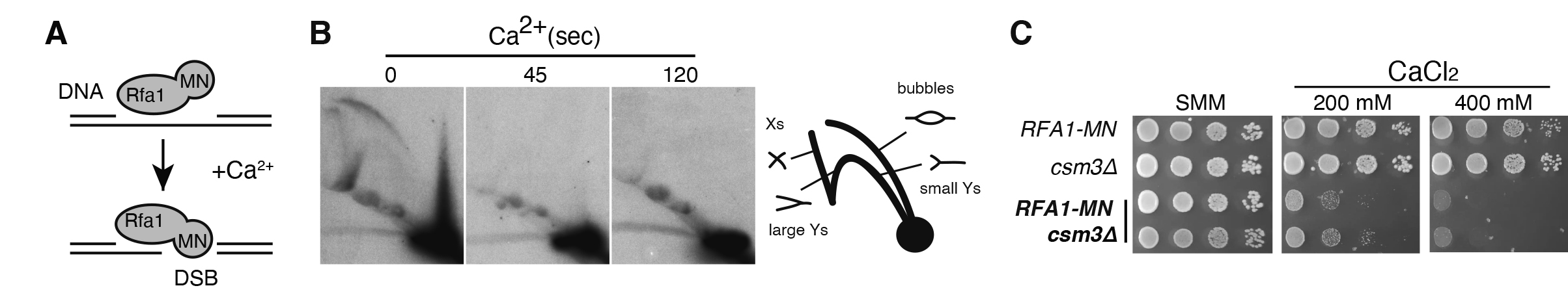

4. Genetic requirements for the repair of broken replication forks: The cellular mechanism that respond to broken replication forks remain poorly understood, despite the fact that genomic instability arising during DNA replication is a hallmark of early cancer progression. A major limitation in addressing this gap is the absence of robust systems to systematically screen for the genetic factors involved. Recently, genetic systems have been developed to induce replication fork breakage via a DNA nick—an intermediate step that is physiologically relevant in DNA repair and topological regulation. However, the cellular response to direct double-strand breaks (DSBs) at replication forks, such as those resulting from fork collapse or unscheduled nuclease activity, remains largely unexplored. In this study, we engineered a chimeric protein, Rfa1-MN, which fuses the largest subunit of the single-stranded DNA-binding complex RPA with micrococcal nuclease (MN). This chimera preferentially generates DSBs at replication forks, enabling us to screen for mutants impaired in fork repair (Figure 1). Our screening identified novel factors that highlight the significance of error-prone break-induced replication (BIR) restart, fork restoration from BIR-intermediates and rescue by converging forks. Specifically, recombination factors associated with replication forks, replisome components critical for fork stability, and regulators of the G1 phase—controlling replication origin number— are potential players to regulate the efficiency of these pathways and the impact of broken fork repair on genome integrity.

Figure 1. A hypothetical role for DDK controlling the integrity of a nucleoprotein scaffold for replication assistance. The MCM complex interacts in yeast with the HR factors Rad51 and Rad52 in a DNA damage and cell cycle-dependent manner. These interactions, which occur at a nuclease-insoluble nucleoprotein scaffold enriched in DNA replication and repair factors, facilitate replication fork progression and ssDNA filling during DDT. DDK maintains these interactions during S phase under conditions of replication stress by preventing the release of these HR factors from the scaffold. DDK might perform this function by controlling either the integrity of the nucleoprotein scaffold by acting upon MCM or the binding of the HR factors to this compartment.

Figure 2. Parental histone distribution and location of the replication obstacle at the nascent strands regulate HR. The recombinational filling of ssDNA gaps is initiated by a strand exchange reaction that reanneals the ssDNA gap with its complementary strand at the invaded molecule, leading to the formation of a sister chromatid junction (SCJ). Defective transfer of parental histones at a nascent strand (mcm2-3a and dpb3 mutants) causes a deficit of parental histones in that strand and a concomitant accumulation of parental histones in the sister strand. Parental histone excess at the invaded strand allows strand invasion but destabilizes the SCJ, which seems to be mediated by an unscheduled recruitment/activity of the antirecombinogenic helicase Srs2.

Figure 3. The chimera Rfa1-MN provides a genetic system to study the repair of DSBs at replication forks. (A) In vitro digestion of replication intermediates by the Rfa1-MN chimera upon calcium treatment. (B) The fork protection complex Csm3 component facilitates the repair of Rfa1-MN-induced broken replication forks.

For a complete list of papers please go to ORCID (0000-0001-9805-782X) or Scopus (7007066781).

Selected publications:

- Ana Amiama-Roig, Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Esther Cruz, Luz M. López-Ruiz, Román González-Prieto, Gabriel Ríos-Orelogio & Félix Prado (AC; Autor de correspondencia). A Rfa1-MN–based system reveals new factors involved in the rescue of broken replication forks. PLoS Genetics (2025) in press Clave: A

- Aurora Yáñez-Vélchez, Antonia M. romero, Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Esther Cruz, Román González-Prieto, Sushma Sharma, Alfred C.O. Vertegaal and Félix Prado (AC). Physical interactions between specifically regulated subpopulations of the MCM and RNR complexes prevent genetic instability. PLoS Genetics (2024) 20(5): e1011148 Clave: A

- Cristina González-Garrido and Félix Prado (AC). Parental histone distribution and location of the replication obstacle at nascent strands control homologous recombination. Cell Rep. (2023) 42: 112174 Clave: A

- María J. Cabello-Lobato, Cristina González-Garrido, María I. Cano-Linares and Félix Prado (AC). Physical interactions between MCM and Rad51 facilitate replication fork lesion bypass and ssDNA gap filling through non-recombinogenic functions. Cell Rep. (2021) 36: 109440 Clave: A

- María I. Cano-Linares, Aurora Yáñez-Vilches, Néstor García-Rodríguez, Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Román González-Prieto, Pedro San-Segundo, Helle D. Ulrich and Félix Prado (AC). Non-recombinogenic role for Rad52, Rad51 and Rad57 in translesion synthesis. EMBO Rep. (2021) 22: e50410 Clave: A

- Román González-Prieto, María J. Cabello-Lobato and Félix Prado (AC). In vivo binding of recombination proteins to non-DSB DNA lesions and to replication forks. Methods Mol. Biol. (2021) 2153: 447-458 Clave: CL Edit. Springer Nature ISBN: 978-1-0716-0646-9

- Tina Wagner, Lara Pérez-Martínez, René Schellhaas, Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Merve Ozturk, Félix Prado, Falk Butter and Brian Luke (AC). Chromatin modifiers and recombination factors promote a telomere fold-back structure, that is lost during replicative senescence. PLoS Genetics (2020) 16(12): e1008603

- Macarena Morillo-Huesca, Marina Murillo-Pineda, Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Elena Gómez-Marín, Marta Clemente-Ruiz and Félix Prado (AC). Actin and nuclear envelope components influence ectopic recombination in the absence of Swr1. Genetics (2019) 213:819-834 Clave: A

- Douglas Maya-Miles, Eloisa Andújar, Monica Pérez-Alegre and Félix Prado (AC). Crosstalk between chromatin structure, cohesion activity and transcription. Epigenetics & Chromatin (2019) 12:47 Clave: A

- Marta Barrientos-Moreno, Marina Murillo Pineda, Ana M. Muñoz-Cabello and Félix Prado (AC). Histone depletion prevents telomere fusions in pre-senescent cells. PLoS Genetics (2018) 14:e1007407 Clave: A

- Silvia Jimeno-Gonzalez, Laura Payán, Ana M. Muñoz-Cabello, Macarena Guijo, Gabriel Gutierrez, Félix Prado and José C. Reyes (AC). Chromatin structure regulates RNA polymerase II elongation rate and co-transcriptional pre-mRNA splicing. PNAS (2015) 112:14840-14845 Clave: A

- Marina Murillo-Pineda, María J. Cabello-Lobato, Marta Clemente-Ruíz, Fernando Monje-Casas and Félix Prado (AC). Defective histone supply causes condensin-dependent chromatin alterations, SAC activation and chromosome decatenation impairment. Nucleic Acid Research (2014) 42:12469-12482

- Félix Prado (AC). Genetic instability is prevented by Mrc1-dependent spatio-temporal separation of replicative and repair activities of homologous recombination. BioEssays (2014) 36:451-462

- Román Gonzalez-Prieto, Ana Muñoz-Cabello, María J. Cabello-Lobato and Félix Prado (AC). Rad51 replication fork recruitment is required for DNA damage tolerance. EMBO J (2013) 32: 1307-1321 Clave: A